Jan 28, 2019

BAFTA Animated Short Film Nominations: How Each Film Was Visually Developed

The animation category at the British Academy Film Awards (BAFTAs) is less predictable than that of the Academy Awards, and the three short films nominated this year are a typically eclectic group.

They do, however, have one thing in common. Two of the directors have already won BAFTAs.

The films are a homage to expressionist painters, to faraway Texas towns, and to old, damaged friendships.

And then there's the fact that, for the first time this century, all of the nominees are hand-drawn, and Cartoon Brew spoke with each of the filmmakers who worked on these shorts about the visual development of their projects.

Elizabeth Hobbs' latest film was inspired by a giant furry mannequin. The mannequin belonged to Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka's former lover, Alma Mahler, and when the two broke up, Kokoschka had it made as a memento (it was later beheaded in public). When Hobbs saw a picture of the doll, she had the idea of telling its story, but decided against it because of its sexist connotations. Instead, she sought inspiration in Kokoschka's astonishing expressionist work from 1912-15, especially his prints and paintings depicting Mahler. [I wanted to make a film about a very dramatic period in Kokoschka's life, when he was wounded as a soldier in World War I and his love for Mahler ended in heartbreak," Hobbs told Cartoon Brew. I wanted to make a film about a very dramatic time in his life," Hobbs told Cartoon Brew. Hobbs didn't use a script or storyboards: "I looked for music he associated with the period, read his plays and writings, studied all his prints and paintings. Then I animated on and around those works."

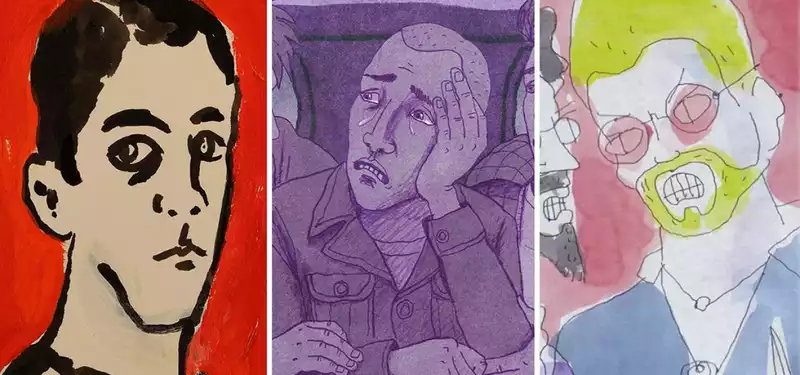

"I'm OK" pays homage to Kokoschka's work, with several frames captioned with the names of specific works. The film was made over and over again for four years," she says, "and that's why it has this style. Had the production period been shorter, it would have been difficult to move away from Kokoschka and establish my own visual language."

The visual language, the breathless colors and fast brushstrokes, are the product of extraordinary working conditions. Hobbs created "I'm OK" alone in one of the bathrooms in her home, which serves as an improvised studio (complete with a rostrum camera). She used acrylic paint and India ink on A5 paper and photographed each frame while the paint was still wet. By doing so, "I was able to create a lot of nice moving sequences, which I could then cut out to create rhythm and drama. I had to reshoot a lot."

The color scheme of the film is particularly striking. The color scheme of the film is particularly striking, with monochrome sections interspersed with naturalistic primary colors. I focused on five colors," she explains. Kokoschka's work was mostly monochrome lithographs, but his work is all about expressionist color, so I tried to evoke that in the film." Except for editing and color grading, Hobbs did not use digital software to process the images. The making of the film is an important part of it," he said. So I'm careful to show the film as it is, even if it's not perfect.

Greg McCloud grew up in the lush Midlands region of England, but when he saw Marfa's photos, the Texas desert town instantly felt like a movie. 'It's a place of big skies,' he said. There's something about it that reminds me of the spaghetti westerns I saw as a kid. The town also has an impossibly vibrant film festival, and when the festival screened "365" (a compilation of one-second vignettes that McCloud animated every day throughout the year), he saw his chance. He would go to Texas and make another animated diary: "Marfa" (a travelogue of his journey to the desert).

Launching a Kickstarter campaign to fund his new work, McCloud set out on his journey, sketchbook and camera in hand. He spent seven hours crossing the arid Texas wilderness to Paris, Texas, listening to stadium country and Ry Cooder's slide guitar scores before arriving in Marfa. His drawings, photographs, and videos serve as visual references to the Marfa scene, each one illustrated with quirky images and anecdotes from his travels.

Back in the UK, McCloud began by arranging the audio tracks. He said, "I went through all the interviews, moods, and music I'd collected and collated clips that would have their own narrative. This set the order of the scenes. Also woven into the soundtrack is a poem by his brother Miles. The poem is an impressionistic collage of words about the Marfa landscape and serves as a tone line for the film.

Like the other brothers' films, "Maafa" is visually economical. McLeod used a 60 gsm economy grade animation paper with ink and watercolor washes. The image is square, with large skies ignored. Color is limited to very little detail and a scene depicting two drugged hitchhikers. My sketchbook was square. 'I intended to shoot it in full color and widescreen. But after many tests, it just didn't work. I went back to the sketches I had made in Marfa and made strong emotional connections. I tried a few times with a more sketchy approach and it really worked"

.

As the credits roll, the last few minutes of the film show a static live-action shot of a freight train barreling down Marfa's tracks. McCloud added this footage on the advice of his friend, documentarian Amy Nicholson. This footage just felt right," McCloud said. It gives us a visual sense of the natural colors of Marfa, and it has the iconic American train sounds in it." I hope audiences will connect the impressionistic animation with the real world"

. [In the 1980s, Jonathan Hodgson burst onto the British animation scene with his punkish, sketchy shorts. After directing several mixed-media documentaries, he returned to his original style with Roughhouse, his first hand-drawn film in 20 years. His earlier work was better received at screenings. I feel more comfortable with hand-drawn animation," he said. I decided to forget about trying to keep up with the times and go back to my roots.

But this decision was also driven by the story. The Rough House is an autobiographical story about the bullying of new students in Liverpool in the 1970s, when Hodgson was studying animation. I wanted to stay true to those times," he says. He not only wrote the script, but also designed the characters and backgrounds, and did all the storyboards and animatics. He used as references his own student work (especially "Nightclub"), as well as photographs, drawings, and memorabilia from his time in the city.

Unable to raise full funding in his home country, Hodgson raised money in France to produce his animations at Studio Train-Train in Lille. There he found that French character animation was "stylized in a different way" than British films. To help his team with the appropriate body language, he showed them footage of his students acting out scenes from the film in London. He also showed the cult live-action film Rita, Sue, and Bob Too. [The film has many of the hallmarks of Hodgson's style, including watercolor-like textures, dynamic camera work, and caricature-like designs. What sets this film apart from his previous works is its bold color scheme. Hodgson was influenced by the woodcuts and lithographs of Edward Borden, who "layered two or three separations of color, and then mixed more colors. I adopted a similar approach in Photoshop, using a limited palette, usually two contrasting colors per scene."

Although Hodgson had used digital software extensively in his mixed media work, this was the first time he had recreated the hand-drawn aesthetic on the computer. The majority of the animation for Rough House was created in TVPaint, and After Effects, "the only 2D software I really feel at home with," was also used for compositing and special effects. The team asked Rainbox Productions to develop a plug-in that would import TVPaint projects directly into After Effects, speeding up the compositing process.

Hodgson remains ambivalent about the transition to digital. He feels that "there is something aesthetically missing in digitally produced animation. Analog drawing has a warmth and authenticity that digital animation seems to lack. [but] economically speaking, it is definitely worth the compromise."

.

Post your comment