Dec 17, 2015

The Difficulty of Making a Car Sing in Claude Cloutier Car Face

We asked Claude Cloutier about the inspiration for his National Film Board of Canada project, Carface.

Here, Cloutier explains the challenges of animating inanimate objects and reveals previously unseen drawings from throughout the film's production.

Carface's film project is the result of a pictorial study dating back some 15 years. At the time, in parallel with the film production, I was drawing portraits of fictional figures made of cars, based on human and animal morphological components. [headlights as eyes, grilles as mouths, and so on.

I wanted to transfer this graphic research to film animation by creating a film based on lip-sync using different shapes of car grilles.

It took me at least a year to find a musical piece that I could use to develop my film: "Que Sera Sera" as sung by Doris Day in Alfred Hitchcock's film "The Man Who Knew Too Much." The song's lyrics express a carefree attitude toward the future.

To me, the song symbolizes the attitude that humans tend to take toward the consequences of their lifestyle. We enjoy the comforts of the modern world without thinking about the negative consequences in the medium term. What happens when we die is not our concern. Moreover, the year 1956, when this song was published, was a time when American automobiles were becoming extravagant in their proportions, shapes, rich chrome plating, and powerful engines. It was the ultimate symbol of postwar prosperity and the boundless optimism of a consumer society.

To illustrate this concept, I imagined a kind of musical in the form of a video clip. The main singer is a 1957 Chevrolet Bel Air. He is accompanied by a chorus and a car of dancers on a Hollywood-style movie set. Moving mechanical parts and Derrick's rhythmic pumping beat.

The score had to be as clear as possible because it had to be made before the animation in order to reference the lip-sync (the first time this technique was used). The original version of "Que Sera Sera" was about two minutes long, too short for the film we had in mind. Our version was extended by adding an instrumental musical bridge before the final refrain. The sound of horns honking, engines revving, brakes squealing, doors and hoods banging...

At this time, he also developed a graphic style and mise-en-scène inspired by American musicals, especially Busby Berkeley musicals. Due to the complexity of the drawing, which involved recreating automobiles in a very realistic style, the challenge was to create the illusion of a blockbuster show while minimizing the animation work as much as possible. To achieve this, we imagined a very fragmented edit with a lot of action happening simultaneously in various scenes: the engine spinning with moving parts under the hood, the earth setting, shots of pumping derricks on the beat, close-ups of the grille singing, the fuel gauge and speedometer shifting, and so on. Wide shots involving many characters were kept to a minimum, and close-ups were used extensively instead. The setting is simple: the film's characters are lit by a projector in a black space.

One of the challenges of the film was to turn inanimate metal into living things by developing a responsive, concrete, and realistic style.

The film was first fully animated in pencil in a very detailed manner, using scale models of collector cars as reference. Then all drawings were traced in a more gestural and quicker way. The drawing was done with paintbrush and Chinese ink and enhanced with a wash of gray. The images were then digitized and a solid coat of transparency was applied using a computer.

The soundtrack and storyboard drawings were then used to create the actual animation. The animation shots were integrated into the animatic as they were completed. Since the overall frame of the film was already defined, new scenes could be created throughout the animation process to the extent that the fragmented composition allowed. This allowed us to change the form as the story unfolded. For this reason, we planned several editing sessions every few months throughout the production.

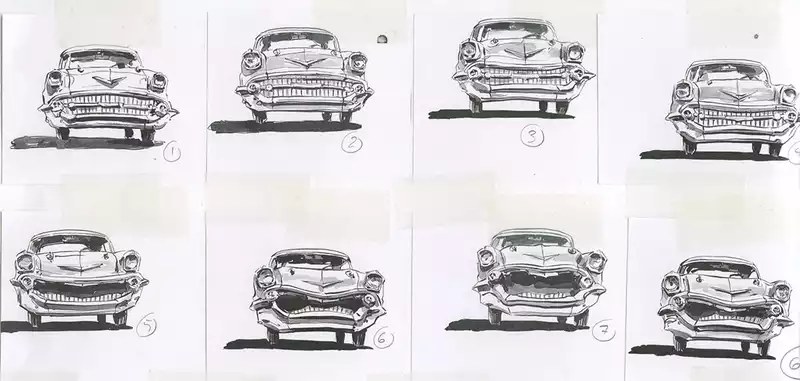

For the singing scenes, we had to draw dozens of different "mouth" positions to synchronize with the editing.

We also added an extra level of highlights to each drawing in the film. Highlights were first drawn in black on a white background, and then the negatives were superimposed on the corresponding car image.

In all, over 4,000 drawings were required.

.

Post your comment