Aug 11, 2016

Ottawa Animation Festival 40th Anniversary Film: "The Man Who Planted Trees

The legendary Ottawa International Animation Festival is celebrating its 40th anniversary this year.

To celebrate, the festival commissioned international animation historians, programmers, and critics to write essays about each grand prize-winning film. In partnership with the Festival, Cartoon Brew will present one essay each week from September 21-25, 2016, through the Festival. Today, we begin with a look back at Ottawa 1988's winning film, The Man Who Planted Trees. For more information on participating in Ottawa, visit animationfestival.ca.

Few animated films combine technical excellence, stunning visual beauty, and social consciousness as well as The Man Who Planted Trees (1987). Directed by Frederick Buck (1924-2013) and produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC), this Canadian film was honored at the Ottawa International Animated Film Festival in 1988.

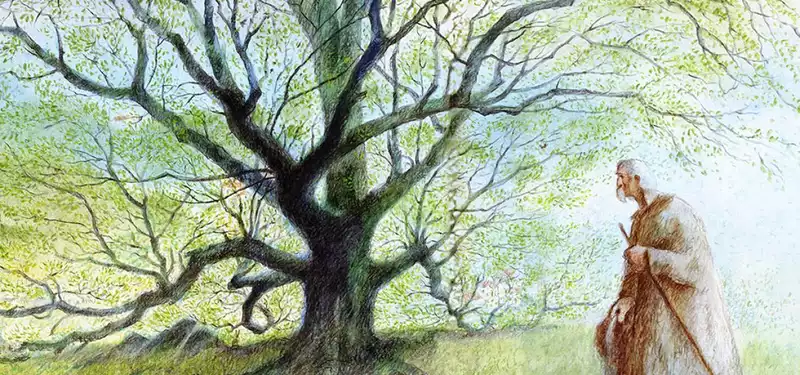

Adapted from the book by French author Jean Giono, the film tells the story of Elzéard Bouffier, a shepherd who single-handedly reforests vast areas of the French countryside. The story is told from the perspective of a young traveler who meets Bouffier and witnesses the land's miraculous transformation from a dangerous wasteland to a lush paradise. The 20,000 photographs used in the film were individually drawn by Buck and his assistant Lina Gagnon.

From a young age, Buck had a deep interest in nature and the treatment of animals. Of these, "The Man Who Planted Trees" bears the closest resemblance to Buck's own life as a dedicated environmentalist. (The in-depth website fredericback.com details Buck's career as an illustrator, television personality, animator, and activist, and offers an extensive biography that explains how he became passionate about his life and work.)

Brewster's work has also been featured in the book "The Man Who Planted Trees.

The most important news of the week, handpicked by the Brew editorial staff, is brought to you every Monday.

Please leave this field empty.

You have been subscribed to our mailing list. You will shortly receive an email confirming your subscription to our newsletter.

Ddocument.getElementById( "ak_js_1" ).setAttribute( "value", ( new Date() ).getTime() );

Hubert Tison, a CBC producer, presented Buck When he read Giono's short story as presented by Buck, he wondered how this story could be adequately translated into an animated form, especially in the proposed 30-minute format. As a result, the script achieved translation in a compelling way, inviting the viewer into a variety of environments, transporting them through visual storytelling and the use of line, color, form, and movement, culminating in an uplifting and empowering ending. The visual elements are amply supported by a soundtrack designed by Normand Roger, an accomplished Canadian composer credited on over 200 animated films.

The film's environments were drawn with colored pencils on matte acetate. The use of pencils allowed for the creation of lines and variations in shading that were not possible with the method of applying paint to transparent cells, which was standard in industrial animation studios at the time. Birds and flight play an important role in the viewer's experience of their surroundings, transporting us in and around a landscape that changes over time. Individual scenes are connected not by cuts that are abrupt and break the flow of the narrative, but by blending through multiple exposures with crossfades and mixes. The narration by Canadian actor Christopher Plummer tells the story as slowly and clearly as the images flow.

The film opens with a scene of barren land painted in black and brown. A black bird flies by, accompanied by Roger's sparkling score, which plays repeatedly at key points in the film. He is a young man on a journey into unknown and hostile territory. The camera pans over still images and dissolves into dilapidated houses and broken churches. The stark lines in the images reflect the effects of the relentless winds that the narrator suggests have driven the inhabitants mad.

The shepherd, Bouffier, appears as a point on the horizon of this environment, seemingly insignificant. Yet after the young man approaches him, the viewer realizes that he is full of life, and that not only he, but also his dog and sheep, are also full of life. The soft, curvaceous lines of these figures contrast with the craggy landscape of the village and its surroundings. The shepherd pours life-giving water and incorporates blue into a background that is only black and brown. Red is also incorporated, for example, in the roof tiles of his well-hewn stone house.

His peaceful experience contrasts with the violent struggle of the desperate villagers, and their experience is portrayed through swirling hands, swords, blood, demons, and madness. This variation draws the viewer in and brings a sense of danger to the already enigmatic events of the story. It is these variations that keep the viewer drawn into the story. The events of World War I are introduced midway through the film, along with violent scenes and confusion, allowing for a new start in the storytelling.

As the story unfolds, color becomes more diverse and applied in greater detail. As we move through the trees planted by Bouffier, blues and greens replace the browns and blacks that dominated the early scenes. One viewpoint looks up at the sky through the trees and spins around in a kind of choreographed movement. Young birch trees are covered with golden leaves, birds fly among them, and leaves float softly. Water flows between the rocks, reflecting the visitor's face, and red, purple, orange, and yellow flowers appear.

The tone of the film changes when the government delegation appears, and many figures, colors, and shapes appear. They are captured in lively close shots, and the point of view flows through the rotating camera, guided by the red and blue birds flying among the leaves. Later, when the forester is invited to the bouffier, the lines shimmer as light falls on them, and the trees dotting the hillside are depicted in a loose, colorful pattern. Walking among the trees, the leaves appear white as they rustle in the breeze, a change from the dark, craggy environment of the beginning of the film.

This brightness continues in the closing scene, as the visitor returns to the area on a bus. The camera swirls around the traveler and even outside the vehicle, intensifying the sense of lightness and flight.

This perception continues in the newer pictures of the village, where the effect of the moving camera, combined with the dissolve, continues the notion of dance and flight. This movement is interrupted by a young woman holding her baby up in the air and by birds moving through the scene. Layers of gardens and trees are shown in close shots as if we are flying through them, horses run through the landscape dissolving various scenes of nature, and colorful images suggest spring and rebirth. These images strongly suggest an Impressionist aesthetic concerned with energy and light.

The film ends by explaining the greatness of this one man and his dedication to making a difference, inspiring the viewer to be empowered as well. It is easy to compare the work of a shepherd to that of Buck, whose life and art were inseparable.

.

Post your comment