Mar 16, 2018

The Tick: Creating a 2,000-foot fully CG man on a TV schedule and budget

In the past, there was a wide gap in the field of visual effects between what was done on film and what was done on television. However, that divide is disappearing, and the types of VFX that effects studios are being commissioned to do for television are becoming increasingly ambitious.

Take, for example, the Very Large Man (VLM) featured in the first season of Amazon Video's offbeat superhero show "The Tick," in which Peter Serafinowicz plays the title character, was a completely digital, almost naked giant modeled after a real-life actor.

Creating a giant CG man on a TV schedule and budget was no mean feat, and Cartoon Brew asked the team at FuseFX, who created the visual effects shots for the VLM, to scan and reference the actors (who were originally intended to appear as real people, not CG) to create these We asked them about the process of scanning and referencing and animating such large characters, and what it took to do this for television.

The initial approach to realizing VLM, a man as tall as a skyscraper and wreaking havoc on the main city in The Tick, was to shoot the actor (Ryan Woodall) against a green screen background and composite him onto a live action plate to achieve substantial effects. However, according to Chad Wanstreet, visual effects supervisor at FuseFX, the problem was that only certain live-action angles could be made completely convincing when Woodle was dressed as a giant.

"The most successful live-action shots were close-ups with minimal depth of field, and wide-angle shots generally speaking did not hold up. So the decision was made early on to go full CG to facilitate the huge environments that needed to be created digitally to sell the scale of the VLM and to ensure proper perspective and atmosphere.

This required the creation of a digi-double VLM. Woodles were scanned in a mobile setup to quickly create the data. Normally, scanning sessions can provide high resolution textures and accurate geometry data for this kind of work, but FuseFX needed to continue building their digital version for their purposes, especially with further sculpting and texturing for the skin FuseFX needed to continue building their digital version with further sculpting and texturing for their purposes, especially for skin.

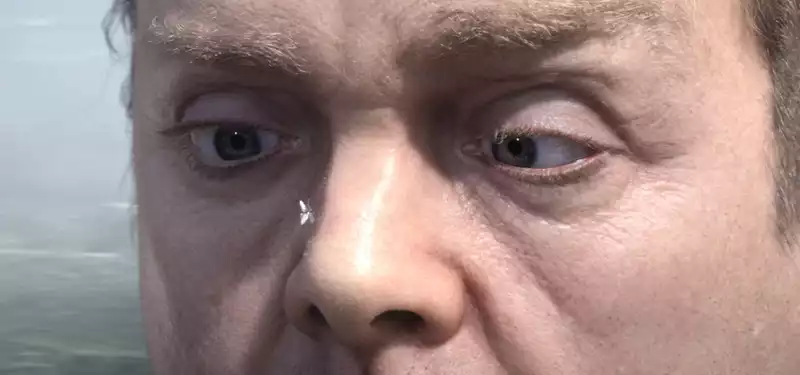

"Due to the massive scale of the VLM, we needed to drive the skin pores based on facial hair stubble grooming to give displacement per pore," said Matt Lefferts, creature supervisor at FuseFX.

"Extra detail was spent to recreate the special details that make the character unique, such as his closed ear piercings, moles, skin blemishes, ear hairs, etc.

VLM's face alone had 15 separate grooms, ranging from light peach fuzz to head and nose hair. Another challenge was the character's CG eyes, which were shown in several close-up shots. One of the keys to the authenticity of the eyes was to make sure the sclera wasn't too bright. "Matching the skin color of the face and slightly reducing the saturation seemed to do the trick. We also modeled a concave shaped "eye water" mesh along the eyelid to give the eyes a watery highlight."

FuseFX rigged and animated the VLM in 3ds Max. Characters were sculpted in ZBrush and texturing was done in Mari. Ornatrix plug-ins were used for hair. Final rendering was done in V-Ray.

Surprisingly, VLM was not brought to life by motion capture. Instead, FuseFX animators keyframed the characters by hand, referencing Woodall's live-action plates. One reason for this was to accommodate scale; CG assets were created to accommodate whatever was needed for a particular scene.

"The character's rig could not be scaled as extensively as would be required for a 2,000-foot man, so the VLM was always rendered for Beauty Pass as a 6-foot man, and the associated environment was rendered at microscale around the 6-foot VLM The environment was rendered at microscale around the 6-foot VLM," Wanstreet says. The VLM was then rendered at 2,000 feet for interaction with other characters and for casting shadows." 0]

"This also meant that every animation for the VLM had to be cached at two different scales, and every shot also had two cameras for the VLM at different heights," Wanstreet added.

"We developed a number of tools to manage the number of assets ingested by the writers who had to deal with the VLM, but Matt Lefferts and [rigging supervisor] Manny Sierra were the managers of the scales associated with rigging and animation.Getting the VLM to look and move properly was a difficult task, but he also had to walk in fields and such. For this, FuseFX typically created a completely digital location and added additional elements to help the character blend into the scene.

"In addition to traditional lens cues like depth of field and chromatic aberration, the fog and atmosphere of the environment were heavily used to shape and give scale to the shots," said FuseFX compositing supervisor Alan Precourt. 2,000 ft. meters, so we used images of skyscrapers, expansive landscapes, and movies like "Arrival" and "Independence Day," which had to deal with issues of scale and proportion as well, for inspiration.

Fuse.

Another particular challenge for FuseFX was managing the complex characters (who also grew and shrank in various episodes) and the various environments they inhabited. In addition, there are scenes in which other characters (often digital doubles themselves) appear along with the VLM.

"We had to tackle three different characters and the environment surrounding the VLM, as well as the interactions with him, which made the work even more complex," Sierra noted.

"Maintaining and updating all the rigs and assets for these episodes was more than a full-time job, it was a logistical struggle.Ultimately, 101 artists from FuseFX's three offices (Los Angeles, New York, and Vancouver) provided the VLM and other visual effects shots for The Tick. The final episode of the first season used 45 full CG shots and 100 visual effects shots, including VLMs and other digital characters.

According to One Street, the studio had the typical time and budget constraints that come with working in television, not only because they had to deliver multiple episodes simultaneously, but also because The Tick is a different kind of superhero show

"The Tick is a different kind of superhero show.

"I think one of the hardest things [about it] was trying to find a style and image that was specific to the genre and world of The Tick," says Wanstreet. With the flood of superhero shows and movies these days, finding an original and interesting visual style is a challenge, and one that myself and the showrunners are constantly trying to develop. It's especially difficult to keep your finger on the pulse of the style when you're delivering hundreds of shots a week in rapid succession, but that seems to be the situation with all VFX-heavy shows these days."

.

Post your comment